The Arab Spring is turning the Muslim world upside down, opening a whole new frontier for brands and marketers. The emerging Muslim consumer is young, tech-savvy and ready to engage, reports Ogilvy Noor’s Shelina Janmohamed and Nazia Du Bois.

The Arab Spring has dominated news headlines since December of last year. The revolutions are changing the face of Middle Eastern and Muslim politics. But what, if anything, can marketers learn from these events?

The popular uprisings were a surprise to many in the West for two reasons: They were persistent and resilient in their drive towards democracy, and they were instigated using peaceful methods.

Muslims today form a majority or significant populations in 57 countries. The Economist estimates that the halal market alone is worth an estimated US$2.1 trillion a year and is growing at US$500 billion annually due to an ever-increasing Muslim population.

Halal itself is an interesting notion, which may appeal to audiences wider than just those who are Muslim. It’s not only about kebabs and curries, but encompasses all products (besides food) that Muslim consumers consider good, pure and produced in line with ethical and Islamic principles.

Understanding Young Muslims

Perhaps most surprising of all to a Western audience that struggles to engage its youth in politics and the public space was that the uprisings were driven largely by young people themselves.

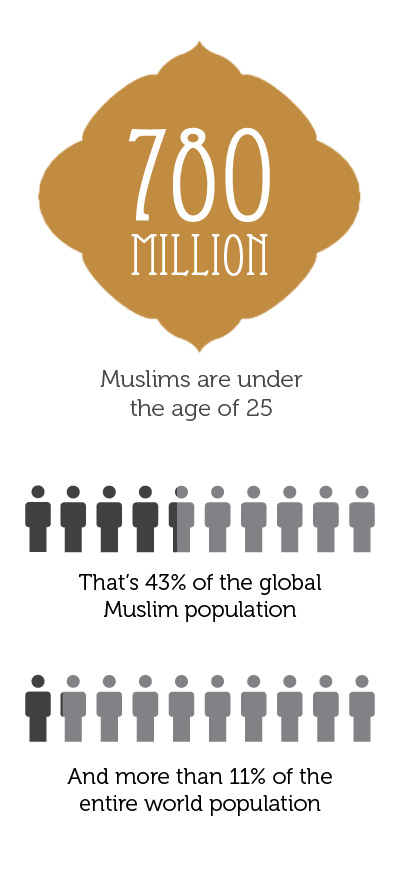

Muslim countries are some of the youngest in the world. The global Muslim population is estimated at 1.8 billion. Of these more than 780 million Muslims are under the age of 25, representing 43% of the global Muslim population and more than 11% of the entire world population.

For marketers who are keen to sow the seeds of brand loyalty at a young age, the Arab Spring ought to be a wake-up call that it’s time to move beyond glib generalizations and get to know Muslims better.

False assumptions

The Arab Spring took most of the world by surprise. For example, Egypt’s peaceful revolution had been impossible to predict, as had Tunisia’s before it, and as have tumultuous events in Bahrain, Syria, Libya and Yemen after it.

But that was because the litmus tests that the outside world had hitherto used to measure what Egyptians were likely to do were flawed. For example, the GDP statistics showed that Egypt was a prospering economy with a population that was doing well.

With a few notable exceptions (like the polls which informed the book Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think, published by Gallup), polls about Muslims focused more on extremism and loyalty rather than values or motivations and drivers.

For those who had looked deeper, what lay beneath the misleading measures were clear signs that young people in particular were discontented. Traditional acceptance of authority was slowly waning amongst younger Muslims who wanted to grasp their own futures with their own hands.

They were using technology, embracing modernity, and seeing no conflict between their faith and a global future. The events told us something that is at once strangely surprising, yet completely obvious: There is more to the Muslim world than veils and violence. Here were people with aspirations, drive, sophistication, creativity and savvy.

Different but the same

The political movements of the Arab Spring were born from a desire for more freedom, better employment prospects and the aspiration to exercise greater self-determination.Brands that wish to engage such consumers at an emotional level have to understand these trends and traits and credit people for their bravery and courage.

Amongst these Muslim billions is a mosaic of cultures and traditions, as well as schools of thought. It is not widely known that most Muslims are not Arab, and not even all Arabs are Muslim. In fact, there are more Muslims in Asia and Africa than in the Middle East.

Wealth also varies with rich economies like those of the Gulf on the one hand, and underdeveloped countries such as Yemen on the other. Some have Islamic governments like Iran, others, like Turkey, are secular.

With this much diversity, why does it even make sense to talk of a global Muslim consumer? Because Islam binds together the daily lives and behaviours – including the consumption habits – of the near 2 billion Muslims in the world. And Muslims themselves will tell you that.

In Gallup’s world poll of more than 35 Muslim countries, when asked what they admired most about the Islamic world, Muslims responded, “People’s sincere adherence to Islam.” And people in virtually all the predominantly or substantially Muslim countries surveyed agreed that, “religion is an important part of life.”

This sincerity of adherence and the way it affects almost 2 billion consumers should be ignored by marketers only at their peril.

![]()